One of my favorite spaces in the world — right up there with Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia, Boston’s City Hall plaza, the Hundertwasser Village — is the Edmond Public Library. It’s nurture as much as nature in my case, as I loved reading almost as much as my parents loved taking me to libraries. But I must admit, I think I strained their patience in one regard: I loved reading Star Wars children/YA novels WAY more than a normal kid should.

Now, my parents are both highly educated, with a non-zero amount of graduate degrees in English Lit between them. They knew that the eighteenth entry in Jude Watson’s Jedi Apprentice series was not exactly the culmination of literary triumph. (I actually seem to remember the quality of each new installment was inversely proportional to how many came before, like how “high-quality” cocaine gets diluted once you’re hooked.) But, I suppose their forbearance came because they didn’t care what I was reading, as long as I took ownership of the pastime.

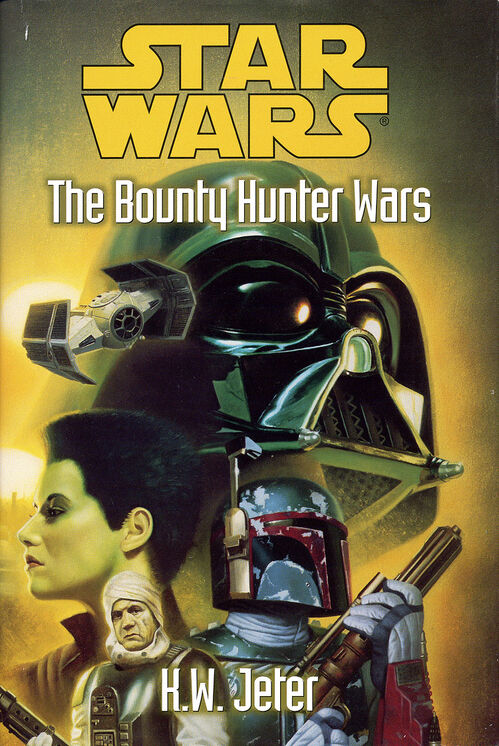

I almost deleted the drug metaphor, but in this case it’s rather apt: I caught the bookworm, bad. My clearest elementary school memories were rushing through my math homework (fractions, ugh) to go down to the library, reading and re-reading entire shelve’s worth of books. A lot of them were books of military history, installments in the excellent Redwall series, and even my fair share of “real” literature (I recall making it half-way through The Two Towers in fourth grade). The wide variety is because even as a fourth-grader, I realized how poorly childrens’ Star Wars novels were written. But once I got to middle school, I discovered adult fiction via K.W. Jeter’s Star Wars: The Bounty Hunter Wars series, which was as well-written as it was compelling — I was hooked on Star Wars novels once again.

The novels follow Boba Fett (perhaps the most famous of Star Wars’ bounty hunters) after he escapes the Sarlaac Pit, and subsequently engages in acts of derring-do and tight-lipped coolness all over the galaxy. I was also an avid reader of Michael Stackpole’s X-Wing series, which I read completely out of order (but I think it follows the rebel pilots of Rogue Squadron in the days after the Empire’s collapse), and started to get into comic books with Dark Horse’s excellent Star Wars: Legacy series (the tale of Luke Skywalker’s great-grandson as he takes on a new generation of Sith). But my favorite series was Republic Commando by Karen Traviss, novels of the Clone Wars from the perspective of the Republic’s most elite soldiers.

Despite those stories losing their canonical status after the Lucasfilm-Disney merger (more on that in a future installment), I still enjoy those stories and keep up with the new ones. My recent favorites have been Marvel’s Darth Vader series, D.J. Older’s Han Solo: Last Shot novel, and literally anything penned by the Midas-touched Claudia Gray. I love these books, not because they’re examples of life-changing literature (please), but because they’re further explorations of a galaxy far, far away; they are the campfire-stories that are the foundation of mythos.

Now, dear reader, let’s shift gears, because so far I haven’t sensed any righteous indignation from you, and if I can’t provide indignation in a timely manner, then I’ve really failed my duty as an Internet content provider. So, my thesis of this week’s installment on Star Wars and hermeneutic: The Judeo-Christian Bible, just like Star Wars, is told by many authors, each with their own predilections, quirks, and perspectives. But far from being a source of alarm, this diversity of authorship is what makes both Bible and Star Wars so compelling.

My reminiscences of my childhood reading habits actually had a purpose, to illustrate constructively what a diverse authorship looks like. By reading the disparate stories of bounty hunters, clone troopers, and Jedi-in-training, I gradually grew to understand anew the galaxy far, far away. No longer was that galaxy a scattering of planets that a Skywalker visited once — it was a teeming petri dish of culture and conflict, where even the backworlds of Jelucan or Akiva have a part in the story of light versus dark. These stories were how I learned that Star Wars characters were biologically capable of intercourse (cheers, Ms. Gray! and don’t worry, dear reader, it’s actually quite tastefully done); how Boba Fett became one of my favorite characters; how I understood the psychology of Vader behind his expressionless mask. Each new author provides a new way to view the characters we know and love.

(Incidentally, this is why I will never take umbrage at a diversity of filmmakers for visual Star Wars media — diverse directors like Irvin Kirchner and Rian Johnson and JJ Abrams each provide a new facet for understanding the Star Wars universe!)

Now, let’s think about the Judeo-Christian Bible in the same manner, as a diverse authorship that collectively constructs greater meaning. The most common objection to this idea is that the Bible is “divinely inspired”, with the implication that God was the sole author of the Bible, and the humans who actually put pen to page were merely God’s instruments. That’s a pretty deeply held conviction I don’t have the space to tackle, but I can recommend those objectors to the excellent podcast The Bible for Normal People, especially episodes 74, 58, and 42, for a nuanced, non-intimidating discussion with experts in Biblical scholarship.

Rather than dealing with the theological question of divine authorship, I’ll focus on a historical-critical approach (which is not mutually exclusive with the notion of divine inspiration, I’ll note!). Among scholars, it’s generally accepted that each of the Bible’s 66 books is written by a different person (or group of people!). For example, 1/2 Samuel is written by an early Israelite source (who I’ll call Sammy), while 1/2 Chronicles is written by “the Chronicler” (whose style is recognizable due to his love for the Levite tribe).* But here’s the catch — both sets of books tell the same stories about the same guy, King David!

And Sammy and the Chronicler have very different takes on David. Sammy recognizes that David was a capable leader, but is unflinching in describing David’s failures in all their salacious details (seriously — 2 Samuel 11 reads like the writing of prehistory’s Zack Snyder). The Yahwist clearly would prefer Israel to be ruled only by Yhwh (see 1 Sam 7.2-17, 8.1-22, etc), and has little patience for the squabbling of Israel’s competing sub-kingdoms.

Meanwhile, the Chronicler is writing from a much later time in Israel’s history, long after the last Israelite king was carried off to Babylon in chains. There are no more Israelite kings, only a diaspora returning at long last to their ancestral lands. Therefore, it’s not surprising that Chronicles views David and the monarchy through rose-colored glasses — even to the extent of omitting the Bathsheba story! And likewise, many of the Chronicler’s stories seem oriented towards healing the rift between northern Israel and southern Judah, welcoming back the returning exiles by treating them kindly through story.

The Chronicler and Sammy are telling stories around a campfire. One spins the tale to warn about the dangers of blindly trusting a monarch; the other emphasizes how wonderful it is to have a united Israel. And they’re not alone in Scripture — heck, we have four different versions of Christ’s life in the Gospels! Can’t you imagine the four Evangelists sitting by a campfire swapping stories, each one inspired by a different aspect of the same divine narrative?

It’s not all that different from Star Wars, where Karen Traviss, Michael Stackpole, and Claudia Gray are trading yarns around a campfire about a galaxy far, far away. And, regardless of how real you find either of these canons — Star Wars or the Bible — these campfire stories are the essence of what makes them resonate with each of us in a very different, very real way.

*These notes were sourced from my NRSV Bible, Revised Edition, general editor H.W. Attridge, but this is a fairly vanilla scholarly consensus.